PLANTING A DIVERSE, POLLINATOR-FRIENDLY GARDEN

Even those of us without green thumbs may have gotten wind of a major issue facing the planet right now. Pollinators—otherwise known as the hard-working bees, butterflies, birds, and other critters that help fertilize the world’s flowers and food supply by carrying necessary pollen from plant to plant—are on the decline. In fact, approximately 40 percent of all insect species have declined dramatically across the globe, due to everything from habitat loss to pollution. Given that one out of every three bites of food we eat exists because of pollinators, says the nonprofit Pollinator Partnership, that’s a pretty major problem . . . as anyone who has ever been hangry can attest.

But it’s not as doom and gloom as it sounds. “It’s not too late to make a difference, but only if we start now and act at every level, from local to global,” Sir Robert Watson, then-chair of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, said in a 2019 report. And if you’re willing to get your hands a little dirty in your own gardens, you—yes, you!—can help. “Nature starts right outside your back door and one way to help nature is to make sure our yards support our very-important pollinators,” says Kris Kiser, President and CEO of the TurfMutt Foundation (www.turfmutt.com). His organization works with partners like the Wildlife Habitat Council and the Center for Green Schools to teach sustainable stewardship of our green spaces and living landscapes.

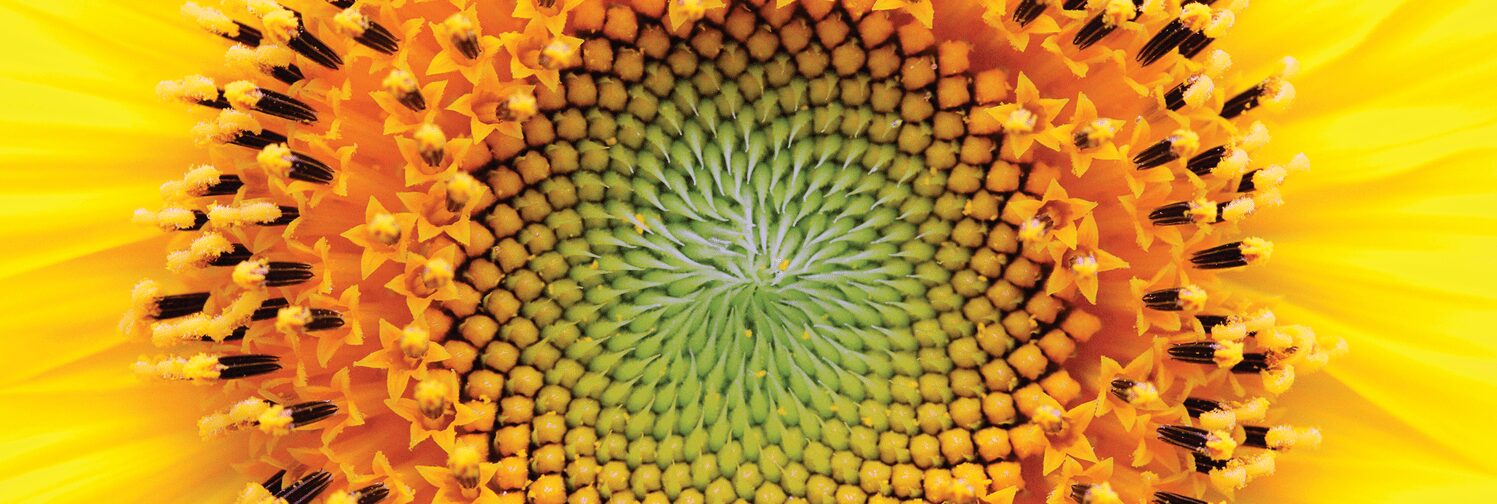

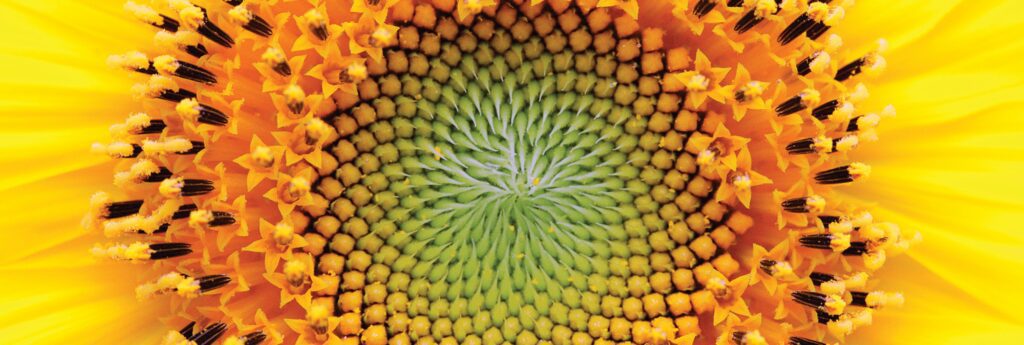

We asked Kiser for his top advice to create a pollinator-friendly garden of your very own. The upshot? You’ll want to get busy as a bee by stopping by your local nursery or garden center. Professional experts there will likely be happy to lend recommendations that will take your local soil types, climate zone, and average rainfall into account. What the birds and bees are attracted to and can digest in, say, South Carolina—where azaleas and sunflowers are a hit—is different from what takes their fancy in Vancouver, BC, where they’re often on the hunt for lavender, rhododendron, and forget-me-nots. “Choose flowering plants for pollinators—butterflies, bees, bats, and hummingbirds,” says Kiser. And don’t limit yourself to one floral species, no matter how pretty it is. You’ll want to “plant a healthy balance of grasses, flowering plants, shrubs, and trees,” he says.

Creating pollinator gardens has become an on-trend approach to alfresco living spaces and is being embraced by local governments and luminaries alike. Case in point: to celebrate the late Queen of England during her Platinum Jubilee in 2022, pollinator plants such as blue cornflower and pink cosmos were arranged in a Superbloom garden within the moat of the Tower of London, to dazzling effect. In Washington, DC at the Smithsonian, an 11,000-square-foot pollinator garden lures hummingbirds and butterflies with native plants year-round. (Caretakers are careful to leave seemingly “dead” plants in place during the winter because even then, they provide crucial habitat for insects).

You may spend a few hundred dollars and a full weekend working on a pollinator garden project, but the juice is worth the squeeze. Kiser notes that 75 percent of the world’s flowering plants depend on pollinators to reproduce (via Pollinator Partnership), and that some 3,500 species of native bees are vital for increasing our crop yields, according to the US Department of Agriculture. Plus, think of the rewards . . . such as dotting your landscape with eye-catching flora and helping ensure there are plentiful strawberries, apples, and even coffee. Talk about priceless.

Bumblebee 101.

Honeybees are the most common pollinators, but bumblebees—their cartoonishly furry cousins—pollinate the plants in our landscapes, too, their wings beating a whopping 200 times a second. Here, fun facts to know about these clever little honeys.

They’re Local. Unlike many bee species, bumblebees are indigenous to North America.

They’re Social. Sure, they’re bees . . . but they’re also social butterflies. Bumblebees live in nests of 50 to 500 of their fellow friends. Their society includes multiple hierarchies à la an insect version of Downton Abbey, including toiling workers and a queen.

They Seize the Day. Unlike the honeybees that migrated here from Europe, bumblebees only live for a year tops. At the end of a summer, their entire colony will pass away, leaving only an emergent (and fertilized) queen to hibernate. She’ll carry on their brood into the next year by laying her eggs, often within the safety of an underground nest. Their unofficial motto? Always bee yourself.